How to Become a Happier Mainframe Professional

Some people might think that working on a mainframe every day is enough to make anyone happy, but as a mainframe professional, what could you do to make yourself happier?

The usual response when people are asked what would make them happier is to suggest that they would like a higher salary and more time off work. But would that really make mainframers happier?

Salary

In 2010, Kahneman & Deaton looked at the effects of a high income. They found that money improves a person’s evaluation of their life but not their emotional wellbeing. Once you reach a certain income, more money won’t make you any happier.

The trouble with money is that it’s comparative. So, if I told you that I was giving you $1 million, you’d be very happy. That is—until you heard I was giving everyone else $2 million! Sonja Lyubormirsky showed in her book, The How of Happiness: A New Approach to Getting the Life You Want, that a person’s salary goals rise as their salary rises. Tantalizingly, you never reach the salary you think you deserve.

Diener & Oishi (2000) set out to investigate whether having plenty of money makes a person happier. They looked at life satisfaction and income in different countries. They didn’t find a strong relationship between the two, which also suggests that having a higher income doesn’t, necessarily, make you happier.

Time Off

If having extra money doesn’t make you happier, what about having more time off? Whillans et al (2016) showed people two examples. There was Tina, who values her time more than money. She’s willing to sacrifice money to have more free time. She’d rather work fewer hours. Then there’s Maggie, who values her money more than her time. She’s willing to sacrifice lots of time to get more money. She’d work more hours to earn more money rather than take time off. The subjects were asked whether they were more like Tina or Maggie, and then how happy they were. The researchers found that people who prioritize time over money, i.e. were more like Tina, were typically happier than people who prioritize money over time. Hershfield et al (2016) also found that people who choose time over money are happier, but they also found around 70% of people choose money over time, and only 30% choose time over money. Cassie Moligner (2010) found that even thinking about time makes a person happier than thinking about money. Their results showed that thinking about time boosts a person’s motivation to socialize—which is associated with greater happiness.

So, maybe, taking more time off will make you happier.

Or, perhaps, you don’t need to do anything really. I’m sure people today with their 60-inch color TV sets and mobile phones must be much happier than people in the past, for example people in the 1940s. Would it surprise you to find that we’re not?! In her book, Sonja Lyubomirsky (again) looked at how life satisfaction in the 1940s compared with more recent times. And guess what? She found that we’re not happier now. Similarly, David G Myers in his 2000 book, The American Paradox: Spiritual Hunger in an Age of Plenty, found that “our becoming much better off over the last four decades has not been accompanied by one iota of increased subjective wellbeing.”

Predictions About Happiness Aren’t Always Accurate

Strangely, asking people what will make them happy doesn’t seem to work well because people aren’t very good at predicting. The problem, it seems, is that most people predict their happiness in terms of absolutes—if I get “X” amount of salary, if I get “X” car or phone, if I get a house with “X” number of bedrooms, I will be a 10 on a happiness scale of 1 to 10. But, it seems, in real life, people compare themselves to other people, as mentioned earlier. Their happiness is relative to other people’s happiness. My four-bedroom house is not that good when my work colleague has a five-bedroom house! People use a relative reference point to measure their happiness rather than (as they predict) an absolute reference point.

Not only are people bad at predicting what will make them happy, they’re also not very accurate at predicting just how happy or sad events are going to make them. They tend to overestimate how happy they will be following a good event and overestimate how bad they will feel following a bad event. Research indicates that people are more resilient when facing bad things and less excited about good ones. Or their estimates are just completely off!

It’s also been found that people get used to good things, and so don’t stay happier than they were previously. This is called hedonic adaptation. This applies to lottery wins, getting married, pay rises, and most other things. Daniel Gilbert in his 2007 book, Stumbling on Happiness, says that “wonderful things are especially wonderful the first time they happen, but their wonderfulness wanes with repetition.”

Mentorship and DEI

Organizations can also help to make mainframers happier. One way to boost happiness in the workplace is through the use of mentorship programs. According to a 2020 survey on the diversein.com website, mentorship has a positive effect on mentees, mentors and their organizations. For example, nine out of 10 employees who have a career mentor say they are happy in their jobs. A 2013 Vestrics study found that mentors’ retention rate increased by 69% and mentees by 72% with mentorship.

According to the CNBC|SurveyMonkey Workforce Happiness Index (April 2021), the Workplace Happiness Index is holding steady with a score of 72 out of 100. The survey found that a majority of the workforce (78%) says it’s important to them to work at an organization that prioritizes diversity and inclusion, and more than half (53%) consider it to be “very important” to them.

Employees’ perceptions of their company’s DEI (diversity, equity, and inclusion) efforts have an effect on their job satisfaction, too. Where workers say their company is “not doing enough” to prioritize diversity and inclusion, their Workforce Happiness Index score is down to 63. People who say their company is doing “about the right amount” and those who say their company is “going too far” on DEI issues have a score of 75 (higher than the average).

Shifting Our Mindset

Mainframers are usually goal-focused in their work, so, shouldn’t they make finding happiness a goal? The answer is “no.” Apparently, trying too hard to find happiness often has the opposite effect and can lead people to be overly selfish. That was the finding of Mauss et al (2012). Rodas, Ahluwalia, & Olson (2018) found that the pursuit of happiness is one place where people should consider avoiding the usual SMART targets because “vague” happiness goals seem to be more effective than more specific ones.

So, what can our mainframe professionals do to make themselves happier? Firstly, they can spend their money on experiences rather than things. Boven & Gilovich (2003) found that it’s better “to do” than “to have,” (i.e. experiences make people happier). And Kumar et al (2014) found that experiences have a longer-lasting effect on happiness.

Another technique to make people happy is savouring. Savouring is the use of thoughts and actions to increase the intensity, duration, and appreciation of positive experiences and emotions. For example, Jose et al (2012) found that savouring positive experiences makes a person happier. And Lyubomirsky et al (2006) found that thinking about life’s positive moments makes a person happier.

Gratitude is another way of increasing a person’s happiness. Emmons et al (2003) found that if a person counts their blessings (the good things in their life), they become happier.

Spending more time with family and friends and other social situations is likely to be more effective in making a person happier than other methods, according to Rohrer et al (2018).

The good news for mainframers is that (once they find it) happiness leads to career success, and it doesn’t have to be “natural” happiness. Walsh et al (2018) found that “experimentally enhancing” positive emotions also contributed to improved outcomes at work!

‘Wants’ and ‘Haves’

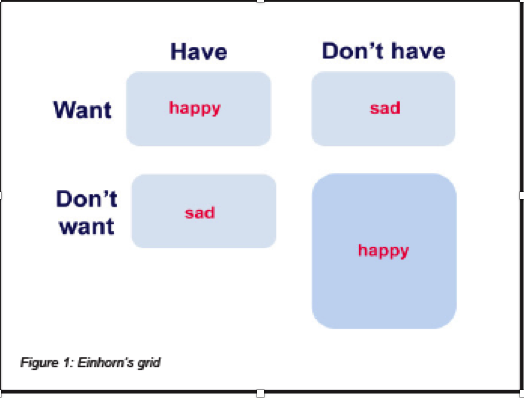

Based on the work of University of Chicago professor Hillel Einhorn, there’s a quick way for anyone to make themselves feel happier. Firstly, they think of all the things there are in the world, starting with their own life and spreading out to include poverty and disease in some countries, extraordinary rendition, cancer, etc. And they must include everything in between. This might take a while.

Then they think of all the things they want that they already have. This might be a nice house, a garden, a loving family, good friends, a new car, etc. These are usually the things around them most of time that they often take for granted, but they are the things they feel grateful for, and give them pleasure.

Next, they think of the things they have that they don’t want. These would be things like extra weight, financial difficulties, a job they don’t like, perhaps some disease, etc. These are things that cause them pain or make them miserable.

The fourth category contains things that they don’t have that they do want to have. These are things like a big lottery win, a new car, better health, etc. These are the things we desire, and we may be motivated to get them, or we may just dream of one day possessing them.

Einhorn notes that people spend most of their time thinking about these last three categories and that’s what they use to define their own happiness.

The final category is the things that a person doesn’t have and they don’t want. This is by far the biggest category. This contains all those horrible things that they thought of at the beginning, plus a whole lot more. These are things that it’s often difficult to think of.

Once a person includes this last category, they realize that they are much happier than they thought. All of us can start counting our blessings once our life is put in perspective.

Einhorn drew a 2×2 table to illustrate a person’s “wants” and “haves” (see Figure 1). Clearly, the largest part is the don’t want and don’t have section.

So, mainframe professionals (and everyone else) can put their happiness in perspective using this technique, and it will probably make them happier.

Stop the Comparisons

If mainframers stop comparing themselves with other people (particularly on social media), that will be an effective way for them to become happier. And spending their money on experiences rather than things, savouring all the positive experiences they have, then thinking about them afterwards, and counting their blessings, are great ways for mainframe professionals to make themselves feel happier. And, perhaps they can work for employers with mentorship programs and strong and effective DEI policies.